When NYC Was Club Kids And Epic Hair

Fashion historian, writer, professor, and independent curator Jessica Glasscock on 90s culture, California summer chic, and the history of the hairpiece.

Hello from a particularly steamy New York City~

It’s 79% humidity with a “Severe Weather” heat advisory, and I’m doing everything I can to not think about this article in The Atlantic on how soon we’ll be able to see the future unfurl through push notifications. (Just some light reading!) It takes a particular breed to be able to withstand summer in the city, when subway platform temps can reach the triple digits and the wildlife gets a little too emboldened. But it’s also when we bring our A Game, with theater in the park, live music almost everywhere (RIP SirenFest), jet-skis taking flight, and a general sense of the metropolis coming alive.

Today’s newsletter is on a place and time that today can feel almost like a dream — when club kids in latex shared the East Village with crust punks and teenage skateboard gangs, Soho lofts overflowed with stretched canvases and revolving parties, and the night streets transformed into catwalks and free-floating casting calls. But more than that, it’s about how fashion can be more than what we wear. It can be about expression, creativity, and fully embodying oneself — whether that’s in French couture or just an old pair of Chucks.

Stay cool~

Laura

Image: “Wigging Out: Fake Hair That Made Real History" by Jessica Glasscock (Hachette) Slow Ghost logo: Tyler Lafreniere

What’s New

See:

CARVALHO PARK’s immersive collaboration between Swedish textile installation artist Diana Orving, New York City Ballet principal dancer Sara Mearns, and celebrated choreographer Jodi Melnick. [July 11, 18, and August 8].

Sunbathing and sound installations at Upstate Art Weekend.

NYC’s beloved Rubin Museum is closing, so visit the bejeweled Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room or go on a Dark Retreat soon.

Read:

How FabriCandy turns fabric waste into beautiful, edible art.

On abandoning 5 year plans.

Visionary designer Halli Thorleifsson’s mission to make Iceland more accessible.

Why Diane Von Furstenburg can’t be held down.

The future of literary America’s favorite highway.

Is AI the end of foreign language education?

Check out:

Danny Lyon's 1960's iconic photo series on American biker culture, the inspiration behind Jeff Nichols' The Bikeriders.

The year in Japanese food festivals.

The world of delightful, esoteric internet interests with the Tiny Awards.

Massively influential French photographer, illustrator, author, and early fashion blogger Garance Doré's new project.

Travel:

For NYers truly sick of the heat, I visited the newly opened The Leeway, a tranquil Catskills boutique motel nestled along a sandy bend of Esopus Creek and can’t recommend it enough. It was dog-friendly, a short ride from Kingston/Woodstock, near plenty of bakeries and hiking, and made a weekend away feel like a full vacation.

Why Lithuania is young, cheap, and chic.

The highly lucrative aquatic semi-secrets of coastal Maine.

How the French have perfected all-you-can-eat buffets.

In praise of gas station pie.

Have an upcoming project, story, or launch? HMU at slowghost@substack.com.

From Wigs to Warhol, Why Fashion’s History is Fascinating

Historian, curator, and writer Jessica Glasscock has spent summers wandering Alaia's Paris archives, made New York's underground 90s club scene her home, and worked for over a decade as research associate at The Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, developing public programming for blockbuster exhibitions like Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty and 2019's Camp: Notes on Fashion.

Jessica has taught fashion history at Parsons School of Design since 2003. She is also a prolific author, with books including Striptease: From Gaslight to Spotlight, American Fashion Accessories (written with Candy Pratts Price), Making a Spectacle: A Fashionable History of Eyewear, and, most recently, Wigging Out, a history of the modern hairpiece.

She is also, above all, hilarious, and an endless font of NYC subculture knowledge. Recently, we caught up with her after an afternoon showing of The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant at Metrograph.

Congratulations on Wigging Out. Can you tell me a little bit more about the process that went into your book?

Working on the book was amazing and very pandemic-y, so it involved a lot of Zoom interviews and digital and online work. I’m a historian, so I’m always enmeshed in established fashion discourse, which is limiting. I think that in some ways, it’s exclusive, but the idea of the wig is sort of beyond that. It’s dress as well as fashion.

I imagine you must have done so many interviews.

It was crucial to talk to makers and those who could provide things I couldn’t learn from just an article. I wanted to speak to hands-on people. I interviewed this incredible hairdresser named Christian, no last name. I met him while studying Stephen Sprouse.

Images courtesy of Deitch Projects.

Was this during your work with the Met?

I knew him through Deitch Projects, where I was working on an exhibition about Stephen Sprouse. He was super generous with his time, so when I was working on the book I hit him up on Instagram again. I’d done research into every bit of his work that had involved wigs. But when I started talking to him, I found out he actually hated wigs. That he was mostly intrigued by natural hair design. What that meant for hair was innovative. When he began working with natural Black hair, he met with a lot of resistance from editors. He’d come up in the late 1960s, peak wig, and done incredible runway hair, which is often very wig-oriented because they want to create a unified vision. So it was amazing to talk to him.

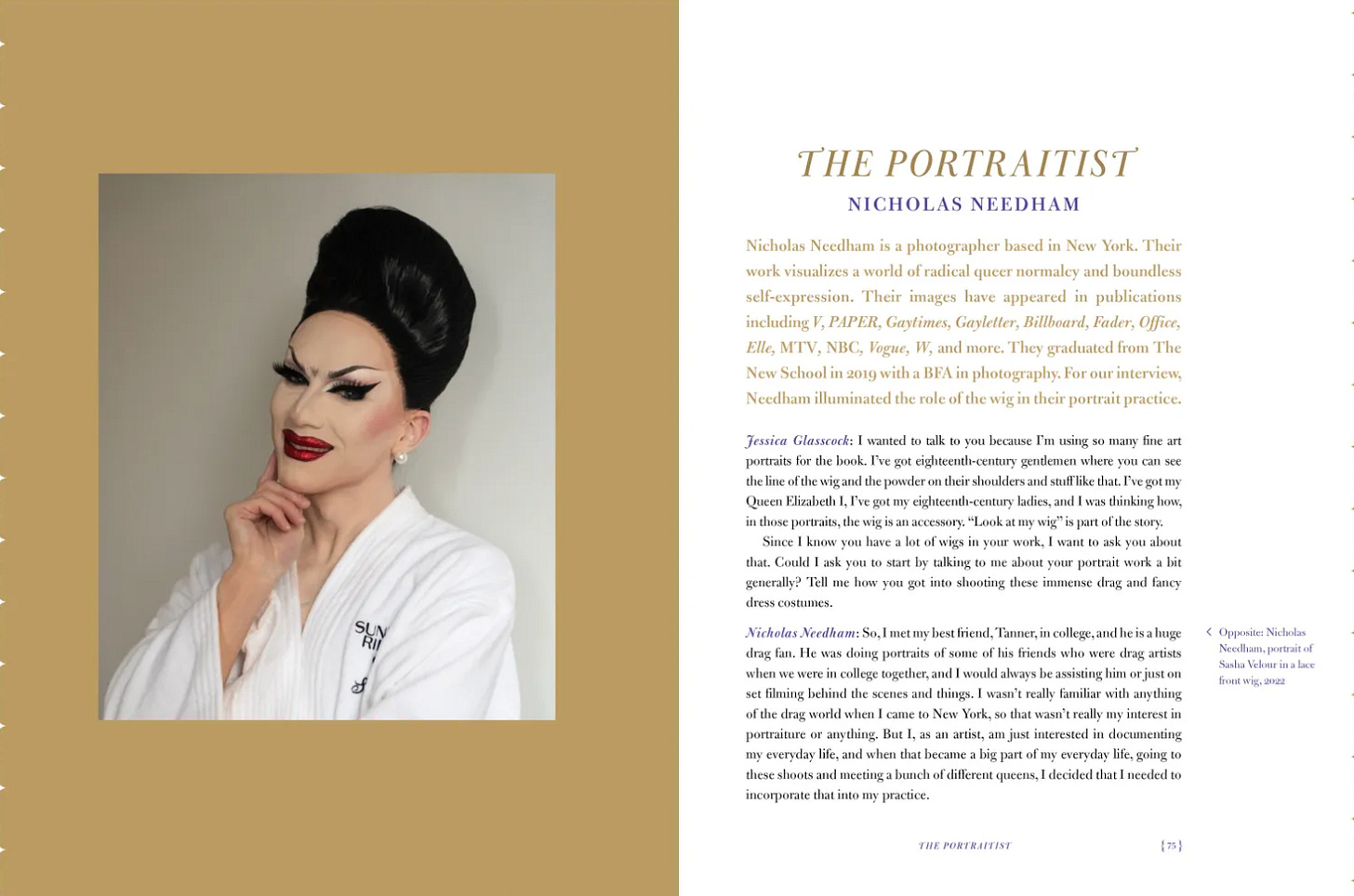

I also spoke to a photographer, Nicholas Needham. A lot of his practice is photographing drag performers. I talked to him about the portrait because so much of my book, when I’m looking for wigs, was a close-up examinations of images online and asking, “Is this a wig? Can I see a hairline? Are there baby hairs? What am I looking at?” I go deep.

That is really deep.

I understood from studying painting how the wig is or isn’t portrayed. Are you trying to show the wig? Are you trying to hide the wig? What’s the story? I interviewed Nicholas as they had worked as a portraitist. How do you hide? How do you show? I also found someone who was a braider, Brieana Spruill, who identified with protective hairstyles for Black hair, so these interviews were an incredible part of it.

People would sit for an hour and I would record. That was a huge learning experience. Talking to makers and creators took me out of my wheelhouse. And I think it brought something deeper to it.

You’ve had an amazing career that hasn’t come about conventionally. You didn’t go to undergrad for Fashion. Would you mind telling me a little bit about what brought you here.

When I was a kid, I would take the curtains and make a dress. Fashion intrigued me, but my mom, a deeply committed feminist and practicing artist, told me “you can do better.” This sense that going into fashion was too feminine. So I decided to do something more supposedly meaningful. I went to college at NYU, where I studied English. I had this idea of going to law school, and then I had this idea of being a bass player. It was the 90s, everybody had a band. Then, I went to work for the ACLU, to champion reproductive freedom and women's rights. And that was powerful and exhausting work. During that time, I began attending the Costume Institute at the Met because it gave me life. At some point in my work with the ACLU, I realized that this fight would always be there, and it could be there without me. Because it was an 80-hour week, it was very intense, and I had this sense that maybe it didn't need me. So I went to graduate school with the view of "I'm going to work at the Costume Institute." That's the plan. And that was the plan! And it worked out.

It definitely did!

Along the way, I also thought that if I went to grad school, I would need to write a book. I'd been involved in the club scene, especially drag, and the Jackie 60 family. It was a cyberpunk scene. A lot of corsets. A lot of rubber. A lot of Prodigy songs. Stuff like that. And I was dressing for that. Radical drag. And also the dominatrix scene. Which was part of that as well. That intrigued me, so I decided, "I'm going to write a book about that scene. And I will gear all of my work in graduate school as research supporting the book." I took a "History of Taste,” class one of the required courses, and our assignment was to compare two magazines. I compared Barely Legal with an S&M magazine and explored their aesthetics and what they accomplished, and my professor just loved that. He thought I was such a badass, ha.

In planning this book, I had a solid two-minute elevator pitch when I graduated and sent it to somebody at Abrams Publishing, but did not think they would publish me. I pitched just to get this editor to evaluate, and what ended up happening is that the next week, The New Yorker published a 10,000-word think piece on the new burlesque. Her publisher brought The New Yorker into their editorial meeting and said, "does anybody have anything on this?" And she mentioned me. So that was my first book. It was terrific, and I had a great time working on it. And I also worked in the registrar's office at the New York Public Library and did freelance curation, and I taught– it was always this, like, big hustle.

How did you start working at The Met?

I was in graduate school and got an internship there because I had an office background and was a paralegal at the ACLU. “We know you’re smart, and you’ll show up on time and know how computers work.” I started working on the museum system, TMS, a database. My first gig was onboarding this data into the process. Some of us get excited about a clean kitchen, and I think if you’re that person, you can do database stuff. It’s all about getting it in order. That was how I got into the Costume Institute. Because I wasn’t a socialite, I didn’t come from money, and I wasn’t that cool. I was cool on maybe Avenue D, but I was not cool at The Met. But I could manage this sort of nuts and bolts detailed information and made that my space there. And that eventually led to a part-time job. This eventually led to a full-time job, a very Met hiring process. You work for free, and then you work for PT, and we give you nothing, and then maybe you get a contract job full-time. I made it through that gauntlet and eventually opened up my work to include educational elements.

I was also excited to share the work, so I started full-time at the Alexander McQueen exhibition, Savage Beauty, which had just opened and was incredible. It was moving and stunning; everybody wanted to see it, and I was new. Every time someone fancy came and wanted to see it, they’d be like, “Jessica, go take this person.” I got to give these fantastic tours of this moving show, which became a part of my gig there. It was sharing the work and articulating it with groups from what I used to call FRPs. Fancy Rich People. But also kids who were coming in as education groups, and kids who were in foster care. It was a peak moment because they were so into it.

Courtesy of A24

Right now you’re very writing focused. Can you talk about your A24 contribution?

A small contribution! Through a friend, I got in touch with a project manager of the recent A24 book on Euphora fashion, the Heidi Bivens book that illuminates her incredible work. They were looking for a fashion historian angle. It was incredibly fun because that’s my idea of fun? It’s like, I know about Converse and Allstars, go! I did it with Chuck Taylors, tennis skirts, and matching sets. Still, I think what was really great was going back and watching the show again, figuring out where the costume designer was coming from, and seeing what kind of elements of the history to really highlight. I wrote this series of three old school, specific garments that connect with characters; Rue is a black Chuck Taylors kind of girl. Jules’s tennis skirt look and the connection with anime Sailor Moon allowed me to then trace back the story of tennis skirts as this sort of sexy thing.

So interesting to see that through line.

I think we think of fashion history as, “when it’s over, it’s over.” Still, I think you’ll find that for me, a historian, from 1800 on, the fashion system that we’re living in now is already in play, and you can find all these stories repeating themselves over and over. And they’re just waiting to be rediscovered. What was funny about the wig was that you saw the play across gender, and the tension on race and all of the things we’re talking about right now in fashion and culture. They have always been thought of as part of the history of this one object.

What is your favorite era of fashion?

I feel like it's hard to let go of the era of your youth. The '90s will always be incredibly meaningful for me, not just because there are some great clothes. But also because it's the moment in which “your fashion” became part of the discourse. All these weird freakish outsider clothes somehow became part of the center of fashion and then stayed there. At the same time, my heart has a special place for the polka dot, Esprit shorts, Valley Girl of the 80s, and Betty for Life. It's very camp. Those clothes smiled. Because 90s clothes are very sour. They don't need you to like them. But 80s clothes are like "love me!"

What’s your next book on?

I have a couple of things in the process, but there are two things I've been interested in going into. The rise of leisurewear and sportswear into a luxury mode. How did leggings come to happen and the arc of that, and Slim Aarons and the 1930s country house and then the discovery of elastic. I've been for years. I'm also tossing something around about club kids. I've been working on that for a long time, and it is also part of my teaching practice. To get into these fantastic creatives. That's what they were. Amazing creatives. It would be interesting to peg something to the arc of Area nightclub, but I'm also interested in these hidden memories that were within these clubs.

What are you working on now?

What I’m very excited about at the NY Historical Society, where I’m currently a rights specialist using my photo research skills. We recently opened “Lost New York”, which is a love letter to the spaces and practices that have defined the city. Old Penn Station, river swimming, let pigs run the street to clean up garbage. This weird town has always been at the center of my research. I'm always psyched to be a part of the storytelling around it.

I think one of the things I’ve said, especially to kids who are younger, they feel such pressure to be One Thing – I tell them you don’t have to. You can take many other turns and they will all feed your practice. By the end, I would rather be in fashion than be a lawyer. My story, especially with women's rights, was fed at the ACLU. When I was in a band in the 90s, it fed my interest, and my cultural style. When you think about your arc – know that it will take you where you should be.

Pick up Wigging Out: Fake Hair That Made Real History here.

Slow Ghost is a newsletter covering creativity now, brought to you by writer and editor Laura Feinstein.