Hihi,

I’m just going to come out and say that this email was supposed to go out in August. Then, well, life happened. Primarily, an extensive road trip through Scandinavia, starting in Copenhagen, snaking up through the Danish Riviera and along the Western Coast of Sweden, stopping in the port of Oslo before heading to the fjords through Lofthus, the “fruit basket of Norway,” before turning back to present on “Manufacturing Materiality” and the fabrics of the future at The Conference in Malmö, Sweden. (If any editors who read this are looking to commission, trust me, I have plenty of material.)

This summer, I also did a deep dive for Wallpaper on how a female winemaker-turned-biotech-perfumer is swapping fossil fuels for fungus, yeast, and sugar; interviewed David Seth Moltz of D.S. & Durga on building a perfume empire from his Brooklyn kitchen for The Creative Independent; and wrote the press release for Mrs. Gallery’s newest show, Body of Work, up through November 2nd. (Read the Slow Ghost on going DIY in the art world and gallerists Sara Maria Salamone and Tyler Lafreniere here.)

Today’s send is on an incredible curator who is taking her practice outside the (white) box and bringing immersive, tactile art from the plains of the Upper Midwest and parks of Chicago to a bog in Upstate New York.

I hope you enjoy it. As always, if there is a creator you think we should highlight, contact me at slowghost@substack.com or in the comments.

~Laura

Slow Ghost logo: Tyler Lafreniere. Image courtesy of Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Read

How the costumes of Gregg Araki’s Doom Generation shaped 90s underground style.

Keel Labs unveils its first seaweed-fiber clothing collection with Outerknown.

The French perfumer behind the internet’s Favorite fragrance.

Is this the rebirth of ABC NO RIO?

A new history of the American worker explores the myths of U.S. exceptionalism.

Check Out

Gothic Knit Club, a haunting, Faulkner-inspired photo collab from the deep south.

This photographic journey into Ghana’s e-waste crisis.

The newest from Conflict Kitchen, a Pittsburgh-based culinary art project that from 2014 to 2017 served cuisine from countries the United States was in conflict with, using food to engage in discussions of cultures and regions beyond headlines.

The Criterion Mobile Closet, a roving replica of Criterion’s legendary film archive built inside an 18-foot delivery van, is bringing its Criterion Closet Picks to Brooklyn Bridge Park and St. Ann’s Warehouse. [Saturday, October 26, and Sunday, October 27, 10 am-6 pm.]

Travel

The strangest and most beautiful spots open to the public for Open House NY.

It’s spooky season in Sleepy Hollow and nearby Irvington, NY — home of author Washington Irving as well as your narrator (hi!). I recommend a tour through the newly restored and perennially haunted Armour Stiner Octagon House, a Gilded Age manor overlooking the Hudson right off Metro North.

If you’re in Europe: road trip to the charming Nordic coastal city of Grebbestad, the “Swedish capital of oysters,” for a schooner ride and an oyster safari (then warm up at Grebys for the seafood buffet).

(Editor’s Note: we’re looking to expand the travel section, so let us know if you have feedback.)

Support

Brooklyn’s beloved indie comic store Desert Island will close if it can’t raise this by October 15th.

For Freedoms and artist Autumn Breon's The Care-Van, a traveling social installation addressing voter suppression and promoting civic engagement.

How To Build A Nomadic Art Museum

An interview with Black Cube’s Cortney Lane Stell

Cortney Lane Stell is the Executive Director and Chief Curator of Black Cube, a nomadic contemporary art museum based in Denver, Colorado. An independent curator since 2006, she has collaborated on numerous exhibitions nationally and internationally for museums, university galleries, biennials, and art events. She has worked with artists like Liam Gillick, Cyprien Gaillard, Daniel Arsham, and Shirley Tse, among others.

Courtesy of Black Cube.

Slow Ghost: I’d love to hear you explain what Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum does.

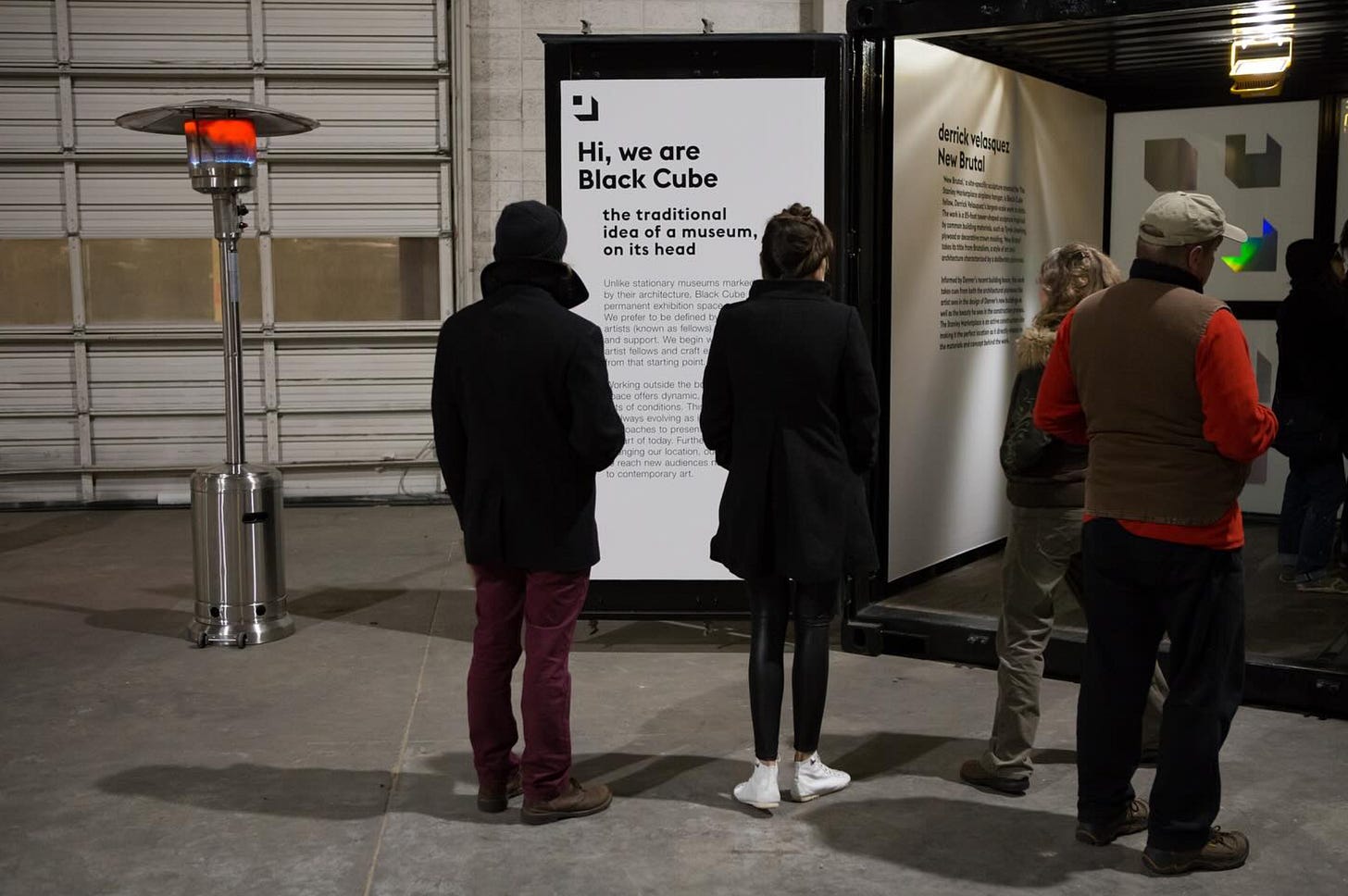

As an organization, we produce site-specific work that increases access to contemporary art and supports creators by producing ambitious projects that move artists’ practices in new directions. We are headquartered in Denver but produce projects regionally, nationally, and occasionally internationally. We collaborate with artists to situate ideas within the context of the world, and have produced projects on historic landmarks, alleyways, ghost towns, agricultural land, tailor shops, cemeteries, and more. We endeavor to help grow artists’ experience, whether working in a new medium, at a larger scale, collaborating with fabricators, reaching specific audiences, or even simply getting the chance to work outdoors. We work closely with artists to produce the projects, not as a studio assistant, but as curatorial and production support and guidance. We also describe ourselves as a nomadic organization. This means pushing against the idea of a traditional institution rooted in one place or community and embracing a structure that is itinerant, slippery, rhizomatic, and dynamic in order to situate art in relation to the world and specific communities.

Interesting.

Many forces in the contemporary art field have created this sort of "big flat nowness" that exists everywhere — the field is laden with white-walled nowhereness that provides a pristine, secularized, religious-type of space allowing audiences to contemplate artworks devoid of context. With the exponential growth of the contemporary art market, museums, and fairs all look the same, and the artists are the same, which has created this hegemony or, what feels like to me, flatness. You'll see one Koons and a similar one at a different museum. The networked era has also supported a social media-based monoculture, where our sense of time is flattened. The upside of this flattening is that people are hungry for context. What's cool about producing art that relates to site, place, community, and/or context is that audiences can find a there —"there" meaning they can connect the work they are seeing to a geographical or sociocultural context, and they can do so largely without art historical knowledge.

Gabriel Rico, La inclusión de mi raza. Courtesy of Black Cube.

Lowering the gatekeepers.

When you place art in the public realm, especially the kind of work that Black Cube produces, it's a unique experience. The work can be approached just as a tree, person, bird, building, or any other object in their environment. We don't overload signage with art historical text or international art English – and we lean into situations that help folks be curious about their surroundings. We're in a moment in society where people are divided. Everyone is becoming more tribal in their belief systems and social circles, and creating curiosity and public space is an opening experience. Black Cube projects wedge the door back open a bit. The organization functions in this unique space to help create connectivity, relationality, and, as I said, curiosity. For example, look at our permanent projects: Community Forms by Matt Barton and Historic Sight by Lenka Clayton and Phillip Andrew Lewis.

That’s so interesting.

Audience engagement must be embraced as a never-ending challenge and opportunity for a moving institution. We once did a project in an airplane hangar on the boundary between Denver and the edge of Aurora, CO. One side had the state's highest per capita household earnings. The other, the Aurora side, had one of the lowest. In this project, we learned it was easier to communicate with the higher-earning community through social media, whereas the Aurora side required hand-to-hand, door-to-door communication. There was a sizable refugee community, so doing this work required sensitivity to all languages and comprehending the nuanced socioeconomic realities to ensure all felt welcome. The other amazing thing about producing temporary projects in the public realm is that they enliven a space and help people imagine different possible futures for it. I've had the privilege of reading lots of visitor feedback.

That is quite a large endeavor.

It's interesting to ideate an organization and then run it. I've learned so much about that gap between theory and practice. Writing a business plan for moving from site to site differs from navigating the changing legal, regulatory, historical, cultural, political, and economic realities that make communities unique. Fundraising also changes dramatically from project to project; it is, for example, much more challenging to fund rural projects. Though the context variability can make the projects challenging, it makes them more vibrant and connected.

Pipelines, Julia Jamrozik + Coryn Kempster

It’s not just curating big experiential public art projects or ribbon cuttings. There's so much behind it.

Yes, we build projects from the ground up and often enfold the community in the research and production of the projects. So, they are not the traditional way institutions present artworks to audiences. We spent two and a half years producing a 160-acre earthwork in a farming community, and part of that involved supporting local food coalition initiatives in the area, as food scarcity was a real issue (which initially felt ironic given it was a farming community).

These projects take time to earn the trust of the locals, especially marginalized or indigenous communities, and it also takes time to generate enough interest for audiences to travel to projects. There are often divides to be bridged; common perceptual clashes include urban/rural divides, outsiders versus insiders, or dissonance between local and foreign. We once did an exhibition in a historic mining town, and it was important to regularly attend town hall meetings to show our participation and commitment. You must find many ways to learn about the community, what folks care about, and what they are challenged by.

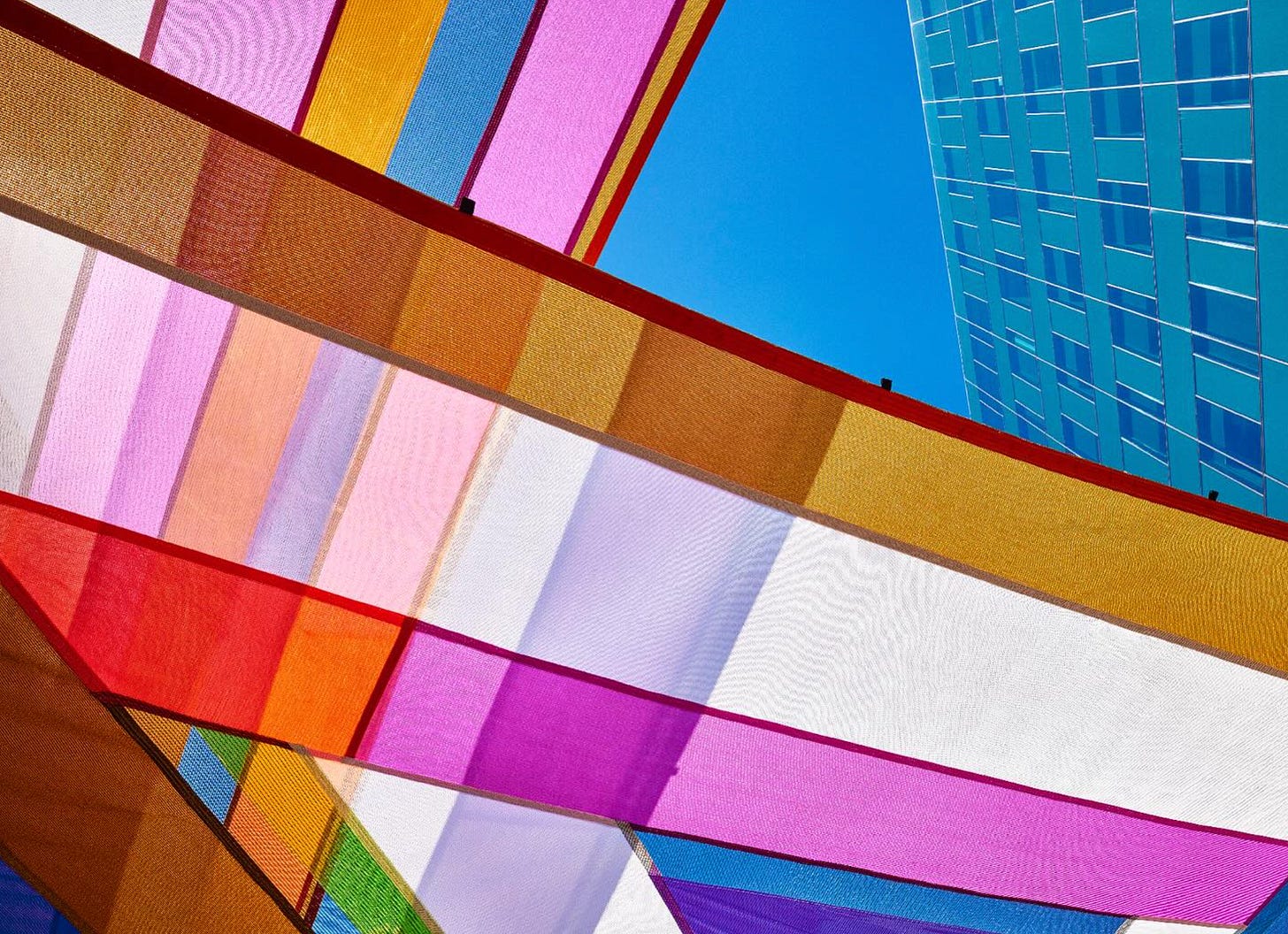

Rachel Hayes, Horizon Drift.

What was your work experience before Black Cube?

Before Black Cube, I had an experimental independent curating practice and was a gallery director at a college for almost a decade. Earlier in my career, after an undergraduate study abroad experience, I spent time living in Italy before returning to Denver to work at a museum in an educational and curatorial capacity within the contemporary art department. Working with curator Dianne Vanderlip was formative, as she curated from a sense of space, which deeply resonated with me. I got close with the curator emeritus at the Denver Art Museum and kept doing independent curating. Nine years ago, I had the opportunity to ideate and establish Black Cube from the ground up, along with the David and Laura Merage Foundation. Now that I've had almost a decade to reflect, I realize I pulled a lot from my experience working as a rave promoter in the early 2000s.

Useless Sacrifice, Anna Uddenberg.

That's incredible.

Rave promotion and production involved scouting sites, getting access to buildings, organizing musical talent, and establishing and nurturing audiences (and much more). More mystery was available for parties in those days as we were not so hyper-connected yet. Maps to parties were often available at specific gas stations. It was before cell phones. It was very DIY. I now see how formative this was for me. Another was growing up with a father in construction and parents who fixed and flipped our houses. We moved around a lot, always thinking creatively about homes, trying to find opportunities, and assessing the communities around those homes. Being in an environment where my parents constantly looked at properties and imagined how they could make them different—thinking about the trees, neighbors, or the community around the houses was interesting. They also had to assess and develop a plan, figure out its feasibility, develop the budget, get all the permits, physically do the construction, and then we would live in the house. My father had his real estate license and would sell the houses himself. Watching my father go through this process of building something from nothing, over and over, gave me agency. It made me realize you can have this big idea but need to break it up into different phases and assess the other skills you need and have. I often saw him take on and move through things that intimidated him. It was kind of like running a small organization.

Between Us: The Downtown Denver Alleyways Project, Group Exhibition, Downtown Denver, CO.

That certainly is an education.

I see now how these experiences have supported my path, but there were also times when I felt like an outsider in the field. Taking a stray cat curator approach and non-traditional routes empowered me with real experience, which has been so helpful in realizing ambitious site-specific and site-relational contemporary art.

I also benefit from being based in the American West, where there's a lot of possibility and often more flexibility and space to embrace untraditional ideas. It’s perhaps a similar quality that many artists in the 60s found in their part of the world: wanting to do something but not knowing how, and committing to figuring it out step-by-step. This, paired with experience, has made me realize how owning this approach is exciting and feasible.

WE ARE BODIES (The Archaeology Files), Anuar Maauad.

“From using raves to funding your undergrad to creating large scale community works.”

I've been on an untraditional educational path. While working as a gallery director at a college, I went to the European Graduate School in the Swiss Alps for my Master's, at a program modeled after Black Mountain College. Some of the leading contemporary thinkers were there, and I had classes with Simon Critchley, Slavoj Žižek, Alan Badou, and other prominent philosophical thinkers and filmmakers like Claire Denis and Catherine Breillat. It was this tiny international school in a town with no cars. I went in the summers, so I was able to work at the same time.

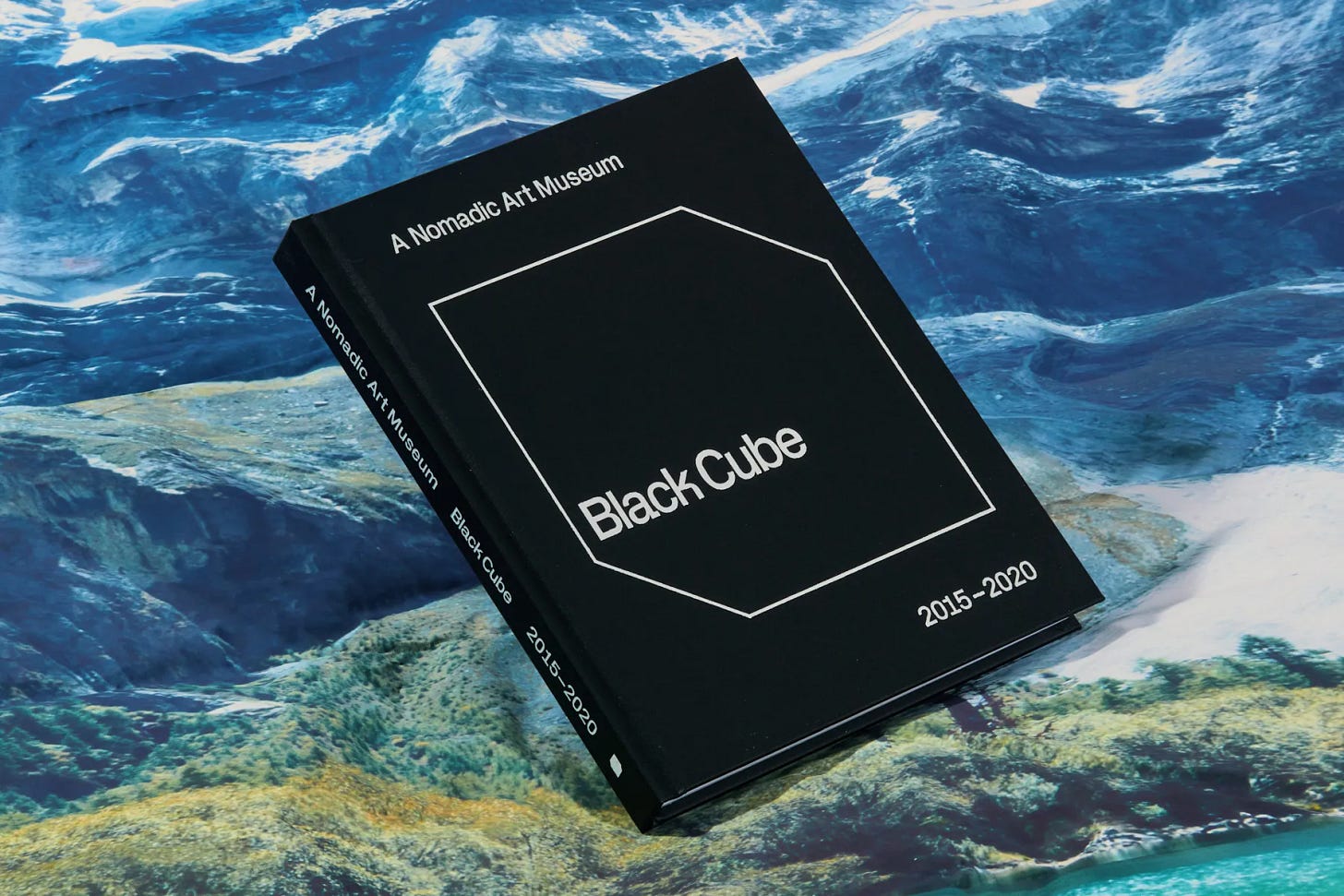

A Nomadic Art Museum: Black Cube 2015 – 2020 surveys groundbreaking, site-specific art projects produced by Black Cube during its first five years, which span across the United States and Europe.

That sounds like an incredible experience.

Many curators go into art history or administration and stay in the field. Still, I'm interested in the world and being around philosophical thought and thinkers shaping contemporary belief. There was an LA Times article about EGS that said students either become unemployable or wizards, and I'm a little bit of both, even though I have a wonderful job. Regardless, we're a weirdo pack of folks. The school is so nontraditional that I was surprised to find it existed when I arrived, even though I had paid all my tuition deposits in advance. It felt like a gamble but opened my mind in many ways.

With each year I work at Kickstarter I have more respect for people who really put everything on the line for their creative projects. If you could make any creative ambitions come to fruition what would it be?

My dream project, that's so interesting. With us, the legacy of working within the community and the process is a big part of it. I've learned not every artist is a good fit, but having a self-aware artist is crucial when producing these high-stakes projects. The quick hit is that I would love to do something on the moon that engages with a collective that somehow expresses the diverse tapestry of humanity and the unity of our species.

Rachel Hayes, Horizon Drift.

The small stuff! Ha. But I don't think that's far flung considering there are now so many artists working on space-related projects.

It may be feasible, but who is the audience? Who is the community? What are the ethics around that? What's rewarding is stepping into a community with openness and humility, being connected, understanding what's important to them and what their challenges are, and collaboratively producing artwork.

To this day, one of my most significant markers of success was a project on the U.S.-Mexico border with Adriana Corral at a former human processing facility called Rio Vista Farms in Socorro, TX. During World War II, there was a program to bring in agricultural and railroad labor. Essentially, processing facilities like these put millions of Mexican men through dehumanizing and unsafe practices. They would go through, get inspected, and essentially enter a gas chamber and be sprayed with DDT or Zyklon B, a chemical later adopted by the Nazis for the extermination of humans. However, all these chemicals and floor plans were initially developed in the U.S.

We started working on this project around 2017 when Trump was at the height of his build-a-wall drama. I was worried about somehow opening up the community to hate; they taught me that this was part of their daily life. I saw how border life was, I visited factories and experienced the inextricable connection between the countries, and I also saw how my perception of the news media was skewed. They were not afraid to talk about border issues. This community, just outside El Paso, dealt with a lot, including poverty, flooding, and other basic needs that were largely unmet. They were also a vibrant and connected community with support systems that I was inspired by. We spent much time with Adriana Corral, the artist, and myself, connecting with Victor Reta, the head of Parks and Rec, to understand the logistical dimensions of working with this site and community. We also connected with Seheila Casper at Saving Places, who helped us understand and honor the historical importance of this site.

After the exhibition, they asked me to participate in their community cookbook. To this day, being invited to contribute has been one of my greatest markers of success, as it showed how we developed deep and meaningful relationships in producing and presenting Adriana's work. So, I don't know what my big dream idea is, but I know that I want to have that kind of impact.

What are you working on now?

We're doing web-based work in New York. Rindon Johnson also partnered with Jordan Loeppky-Kolesnik to create chromed sculptures placed in a wetland site that look almost alien against the landscape. We're building the website and will have webcams on the sculpture so you can view them day or night through all the seasonal changes. These sculptures are placed within the flooding zone of a forested area, so they'll change dramatically.

Rindon Johnson and Jordan Loeppky-Kolesnik, "Sitting a little way off, beyond the trees, so as to remain in the full ambit." 2024. Installation view, Saugerties, New York.

That’s so interesting.

Last April, we also opened a project in Chicago with the artist Brendan Fernandes titled New Monuments | Chicago. It's the first in a series we're working on with Brendan, a choreographer who does public interventions around monuments. His work focuses on creating spaces of hope and possibility, particularly around places with historical significance or monuments to white colonial figures inconsistent with their surrounding communities. Getting the green light on the project was challenging, particularly with current conversations around contentious monuments.

Chicago-based artist and 2022 Black Cube Artist Fellow Brendan Fernandes, New Monuments | Chicago. Presented in association with the Chicago Park District. Architectural Intervention by AIM Architecture.

Tell me more.

During the uprisings in 2020, Chicago experienced a lightning rod moment around the Columbus Monument at Grant Park. Former mayor Lori Lightfoot removed it in 2021 under the cover of night. Even though the City of Chicago has audited its monuments since then, it was still cautious about engaging monuments because of safety factors. New Monuments | Chicago was greenlit at the beginning of February 2024, meaning we had just a few months to execute this complicated project. The work ended up being a sculptural intervention around the General John Logan Monument, the second most prominent after Columbus.

The Logan Monument is interesting because Logan is a complicated figure. He was celebrated for his work in local government before becoming a general, then worked within the federal government and became the founder of Memorial Day. But earlier in his career, he passed legislation prohibitive to Black people in Illinois during the Great Migration. Later, when he experienced firsthand the oppression of minorities, he evolved and helped legislate, including for women's rights.

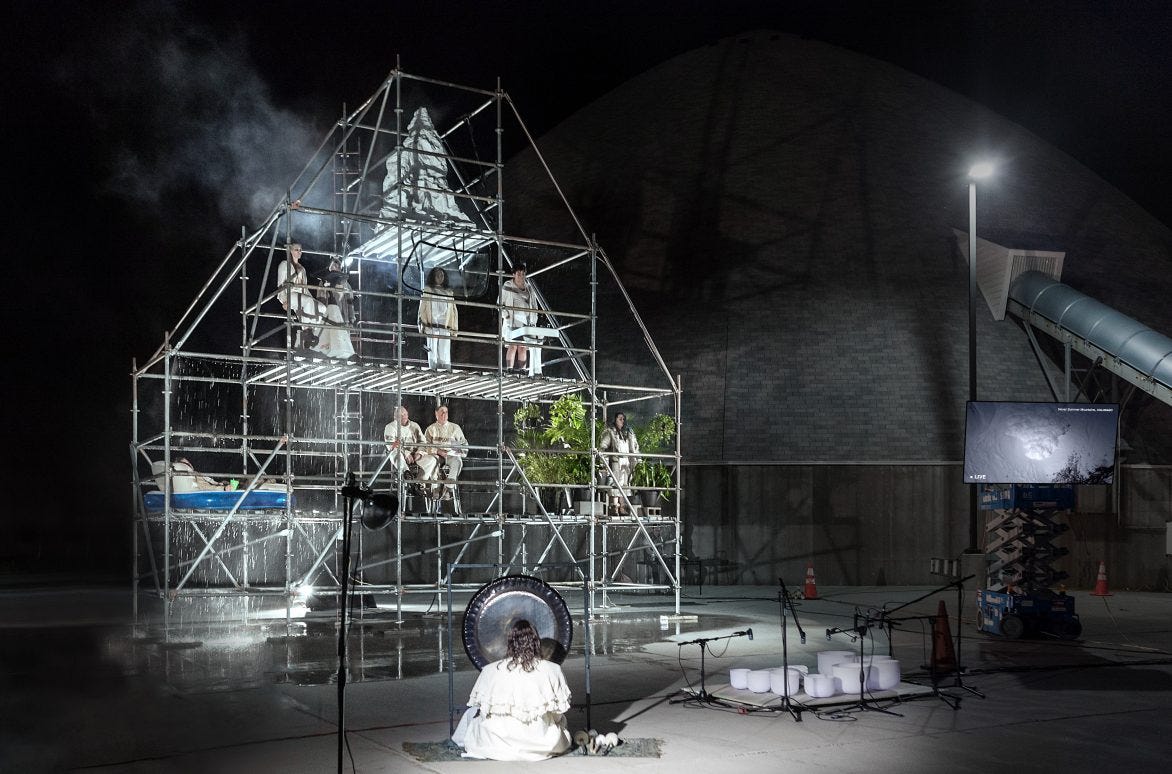

The sculptural intervention around the monument was made with mirrored materials, making it look like a prism. At some point, mirrors were perpendicular to the sculpture, and the scaffolding was intended to make the space look like it was in transition. "Was it coming down? Was it being restored?" The mirrors reflected the city and the audience. We received support from AIM Architecture based in Shanghai, who designed the scaffolding, and had a choreographed performance at night to reference Lightfoot's gesture. We also had a written prompt: "How can we become a monument?" We developed silver tags with paperbacks where people could write their responses and a shipping container on site staffed by gallery attendants where people could fill out the prompts, which were displayed en masse. We also placed kiosks with tags throughout the city at different cultural institutions to broaden that outreach. It was so cool to see the community respond to these prompts.

Truly.

When you do something in a public space, you never know the response or if the community will be receptive, and we had more responses than expected. With Brendan Fernandes’ work, people were walking by, and some were upset, asking, “Is this under construction?” or “Are they taking it down?” Others, in turn, were like, “Just tear it all down.” I know we are doing good work if audiences have strong options, either positive or negative. After all, I feel that stimulating space with the remarkable visions of artists is truly magical only when it meets the public.

Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum. All images courtesy of Black Cube.

Slow Ghost is a newsletter covering the next wave in culture, brought to you by writer Laura Feinstein.